After visiting Japan, I was jolted into a completely different society again. We made our way to Korea where the streets plentiful trash cans and beggars. Instead of feeling guilty for bumping into someone on the subway, it was perfectly normal to do so and not even have to say sorry. People were chattering with each other even though they were strangers and also wanted to interact with us foreigners. Just walking around in the hotel in South Korea, it felt like Los Angeles, but replaced with an Asian population. The loss of security found in Japan was immediately lost when I stepped foot into South Korea. The South Korean culture has much compassion for each other, which gave them a sense of community that the Japanese people find only when shopping. However, after visiting Paju Book City, the vibrancy of these people and prolonged excitement of the city disappeared.

Paju was established by publishing companies and other support services of the bookmaking process. Because literature holds the power of intellectual development, Paju started to have an elitist take. It became this utopia where every building was perfect in its own individual manner. Upon arrival, I stared in awe trying to comprehend where I was. Growing up in Los Angeles, I was accustomed to seeing “ugly” buildings. Everywhere I looked, each building was designed and executed using a simple diagram.

Paju was established by publishing companies and other support services of the bookmaking process. Because literature holds the power of intellectual development, Paju started to have an elitist take. It became this utopia where every building was perfect in its own individual manner. Upon arrival, I stared in awe trying to comprehend where I was. Growing up in Los Angeles, I was accustomed to seeing “ugly” buildings. Everywhere I looked, each building was designed and executed using a simple diagram.

Panning out from the individual buildings, I started to look at the area as a whole. There was too much uniformity of being unique, which made it all the more ordinary. On paper, it seemed that having a wholly designed area would be great! But actually walking and experiencing the reality of Paju completely changed my perception. If there were only a few well designed buildings, I would be able to appreciate each one as I came across it. Obviously each building had its own individual expression, but as a collective, the imperfection disappeared. Now that each building has its own individual identity, does a cluster of unique buildings still give each building the same individuality?

Why did Paju leave me desensitized while Tokyo and Seoul always kept me engaged? First of all, the city was inaccessible by the subway other than transferring part of the way there from one. Also, I had to take a bus to reach it. Lacking infrastructure diminishes a great amount of people flow to the city, which is why it felt so empty. However, if it was the intention of the publishers to keep Paju isolated from Seoul, they seemed to have gotten the right effect, but as a consequence eliminated the humanistic qualities found in a REAL city. It is the sense of a city’s humanistic qualities that can be critiqued and improved on the most. Yet, because of the lack of this and buildings are well designed, there is barely any dialogue or narrative between human and “city”.

Urbanistically, the only ties within each neighboring building was a weak and unsubstantial patch of garden or landscape. The buildings did not respond to each other and if they did, the city would have had an additional level of cohesiveness that could be appreciated. However, if the city eliminated the garden to construct a new building, the already weak link would be gone and completely sever the dialogue between buildings. In Tokyo, I was always actively engaged because the Shiodome buildings had a unifying dialogue through multiple levels. On the third floor, there was the sky bridge that placed me above the cars and had appropriate access points back to the ground level. At the same time, there was also the ground and subterranean levels that did the same. This high level of engagement is what always kept me on my toes and why walking through Paju was so desensitizing. Paju was missing the multiple layers of human engagement and only used the ground plane to “connect” all its buildings. Paju’s greatest asset of being a designed city became its greatest flaw by not being fully designed.

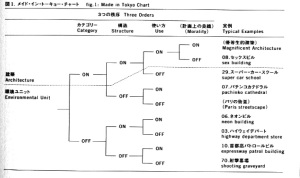

Cities like Tokyo, Seoul, and Hong Kong all have infrastructure as their main system to bring people into different parts of the city. Having a fully designed development like Paju is not the only ingredient to have a “utopian” city. Paju only has only superficial elements to call itself a “city.” They have avenues, streets, offices, factories, shopping, and other needs that a REAL city has, but lacks the REAL designed aspects of a city. A REAL city has systems, efficiency, and programs to help facilitate the urban construct of people occupying a city. The introductory segment of Made in Tokyo the following chart:

The chart shows a series of possibilities with off and on switches. There are 3 main criteria that compose the “Environmental Unit”: category, use, and structure. When describing architecture, morality becomes a fourth option. The Environmental Unit describes an instance of strange coherency between programs that are seemingly unrelated. Paju would be described with all switches on, making it a “Magnificent Building.” However, cities like Tokyo, Seoul, and Hong Kong all have at least one off switch in the “Environmental Unit” criteria. They can be what Made In Tokyo described as “Da-me architecture (no-good architecture)…they seem to be better than anything designed by architects.” The buildings in developed cities have a clash of unrelated programs within the same confinement, but it is this tension that describes the actual city than the city itself. The multiple layers of subway, retail, hotel, and restaurant within a buildings corresponds with a variety of social purposes. The building becomes this mixing pot of activity that captivates an foreigner’s attention like myself. However, Paju lacks the tensions and layering of buildings, making as boring and as similar to single-family suburban homes.

Could Paju then be considered a real city? Based on the evaluation that it lacks the substantial components of a city, it is at most a “real-fake” city that prides itself on having only unique architecture and the superficial elements that comprise of a city. Paju can eventually transform from a “real-fake” city into a REAL city only if it sheds its singular building monument-like attitude and adopt a more urbanistic approach where these buildings still have their own image, but when all of them are added as a whole, makes Paju something more.

_Joyce

Filed under: Collective, Culture, Desensitize, dialogue, Fake-Real, Japan, Korea, narrative, Paju, Psyche, tension, Utopia